Over the last several decades, organizations across manufacturing, energy, utilities, transportation, and process industries have invested heavily in maintenance programs with the intent of improving reliability, safety, and asset availability. Preventive maintenance schedules have expanded, inspection routines have multiplied, and digital tools have made it easier than ever to generate work orders. Yet paradoxically, many organizations now experience higher maintenance costs, stagnant reliability metrics, and recurring equipment failures despite doing “more” maintenance than ever before.

This phenomenon is increasingly recognized as over-maintenance, a condition where excessive, poorly targeted, or misaligned maintenance activities themselves become a dominant source of failure, cost, and operational inefficiency. This article examines over-maintenance as a systemic failure mode, explores the mechanisms through which it degrades asset performance, and outlines a more evidence-based, reliability-centered approach to maintenance strategy.

Understanding Over-Maintenance in the Context of Modern Reliability Management

Over-maintenance is not the absence of discipline or effort; rather, it is the misapplication of maintenance effort. It occurs when maintenance tasks are performed more frequently than required, without clear linkage to failure mechanisms, or without demonstrable impact on risk reduction. In many cases, over-maintenance emerges from good intentions—risk aversion, regulatory caution, or historical precedent—rather than from negligence.

In traditional preventive maintenance models, tasks are scheduled based on elapsed time or usage, often derived from vendor recommendations or legacy practices. While such approaches may reduce certain early-life failures, they frequently ignore how assets actually fail in real operating conditions. When time-based interventions are applied indiscriminately, they may disrupt stable systems, introduce variability, and accelerate wear processes.

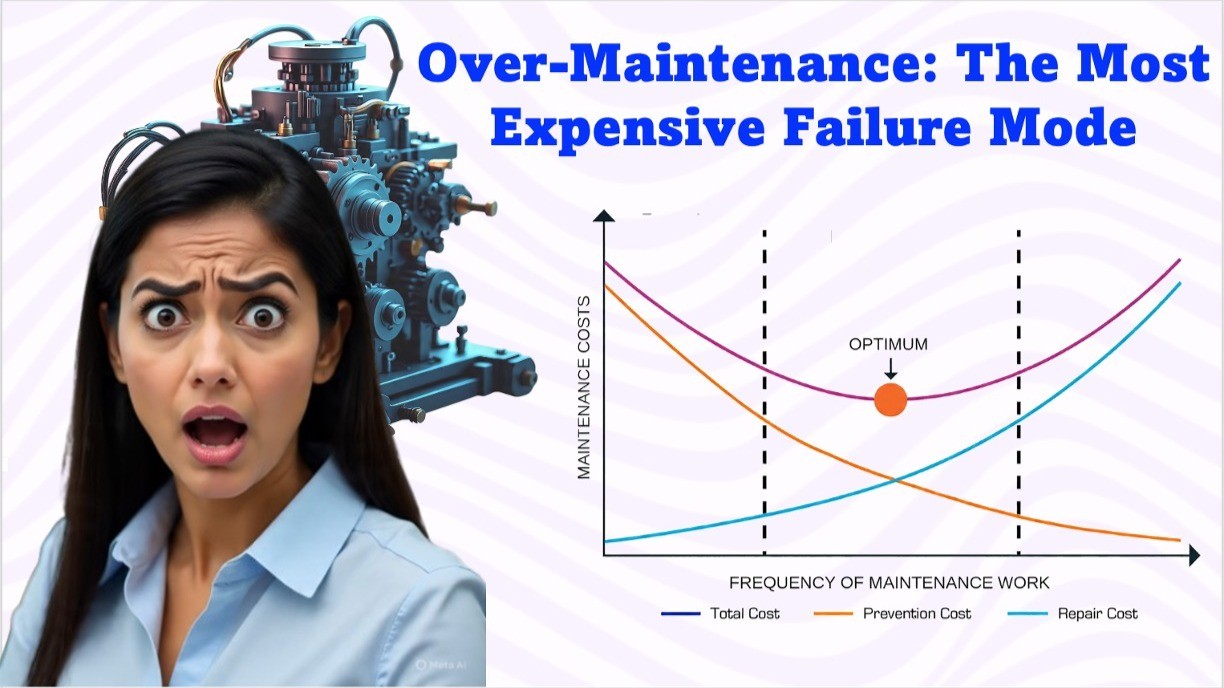

From a reliability engineering perspective, over-maintenance represents a loss of alignment between maintenance actions and dominant failure modes. When alignment is lost, maintenance transitions from a value-creating activity into a cost-amplifying one.

Why Over-Maintenance Qualifies as a Failure Mode Rather Than a Cost Issue

A failure mode is traditionally defined as the specific way in which an asset or system fails to perform its intended function. Over-maintenance fits this definition because it actively contributes to functional failure, not merely to excess spending.

Each maintenance intervention introduces risk. Components are disassembled, fasteners are loosened, clearances are altered, and human judgment is applied under time pressure. While necessary in many cases, these actions can degrade reliability when performed unnecessarily or too frequently. Over time, the cumulative effect of excessive interventions can surpass the failure risk they were intended to mitigate.

Thus, over-maintenance should be treated not as a budgeting problem, but as a reliability hazard embedded within the maintenance system itself.

The Reliability Science Behind Why More Maintenance Can Increase Breakdowns

The Physical Degradation Introduced by Excessive Maintenance Interventions

Mechanical and electrical systems are designed to operate within stable configurations. Excessive maintenance disrupts this stability. Bearings that are repeatedly removed and reinstalled may experience misalignment. Electrical connections may suffer from repeated loosening and tightening. Seals and gaskets may be compromised by frequent replacement.

From a tribological and materials science standpoint, many components experience higher failure probability immediately following maintenance. This phenomenon, sometimes referred to as “infant mortality after maintenance,” reflects the reality that intervention itself can initiate new failure pathways.

Human Error as a Statistically Inevitable Outcome of Excess Maintenance Volume

Human reliability analysis demonstrates that error probability increases with task repetition, time pressure, fatigue, and task complexity. When maintenance schedules are overloaded with low-value tasks, technicians are required to perform more work in the same time window, often under constrained shutdown periods.

As task volume increases, so does the likelihood of:

- Incorrect reassembly

- Missed steps in procedures

- Improper calibration

- Installation of incorrect or defective parts

Over-maintenance therefore increases exposure to human error, transforming maintenance teams from reliability protectors into inadvertent sources of failure.

The Distortion of Failure Data and Reliability Metrics

Over-Maintenance: The Most Expensive Failure Mode

One of the more insidious consequences of over-maintenance is its impact on data quality. When assets are frequently disturbed, it becomes difficult to distinguish natural degradation trends from maintenance-induced anomalies. Mean Time Between Failures (MTBF), failure distributions, and condition monitoring baselines become unreliable.

This distortion leads organizations to misinterpret asset health, often prompting even more preventive tasks in response to perceived instability. The result is a self-reinforcing cycle of intervention and degradation.

Economic Implications of Over-Maintenance Beyond Direct Maintenance Costs

While labor and spare parts costs are the most visible consequences of over-maintenance, the true economic impact extends far beyond the maintenance department.

Excessive maintenance increases planned downtime, which reduces asset availability and production capacity. It also inflates inventory carrying costs, as organizations stock spares for tasks that provide little reliability benefit. Engineering and supervisory resources are diverted from improvement initiatives toward managing unnecessary work.

Most critically, over-maintenance imposes a high opportunity cost. Capital, labor, and management attention consumed by low-value activities cannot be invested in process optimization, technology upgrades, or workforce capability development.

Organizational and Cultural Drivers of Over-Maintenance

Risk Aversion and the Misinterpretation of Control

Many leadership teams equate visible activity with control. A dense preventive maintenance schedule creates a sense of reassurance, even when empirical evidence does not support its effectiveness. In highly regulated or safety-critical industries, this tendency is often amplified by fear of non-compliance or catastrophic failure.

However, excessive maintenance does not equate to reduced risk. In fact, unmanaged over-maintenance may increase operational risk while creating an illusion of safety.

Legacy Practices and the Persistence of Outdated Maintenance Philosophies

Maintenance programs often evolve incrementally. Tasks are added over time but rarely removed. A failure event may lead to the introduction of a new inspection, but successful operation rarely triggers task elimination. Over years or decades, maintenance plans become bloated with activities that no longer address current failure mechanisms.

Without periodic critical review, organizations inherit maintenance strategies optimized for conditions that no longer exist.

Identifying Over-Maintenance Through Diagnostic Indicators

Over-maintenance rarely announces itself explicitly. Instead, it manifests through a pattern of symptoms that, when viewed collectively, point to systemic inefficiency.

Organizations experiencing over-maintenance often report:

- Increasing maintenance workload without corresponding improvements in availability or reliability

- A high proportion of work orders closed with “no fault found”

- Rising corrective maintenance shortly after preventive tasks

- Technician fatigue and declining morale

- Escalating maintenance costs despite stable or declining asset utilization

These indicators suggest that maintenance effort is decoupled from reliability outcomes.

Transitioning from Over-Maintenance to Reliability-Centered Maintenance

The Role of Failure Mode Understanding in Eliminating Unnecessary Tasks

Reliability-Centered Maintenance (RCM) provides a structured framework for aligning maintenance tasks with actual failure mechanisms. By systematically analyzing how assets fail, why they fail, and what the consequences are, organizations can determine which maintenance actions are technically feasible and worth performing.

RCM frequently reveals that many time-based tasks have little or no impact on failure prevention. Eliminating or redesigning these tasks is often the first step toward reducing over-maintenance.

Condition-Based and Predictive Maintenance as Antidotes to Over-Maintenance

Condition-based maintenance (CBM) and predictive maintenance (PdM) shift the focus from time to evidence. Maintenance is performed only when data indicates a developing failure condition. This approach reduces unnecessary interventions while improving early fault detection.

However, technology alone is insufficient. Without proper alarm management, data governance, and decision rules, predictive tools can generate false positives that actually increase maintenance activity. Effective implementation requires discipline, validation, and continuous learning.

Leadership Responsibilities in Preventing Over-Maintenance

Over-maintenance is ultimately a leadership issue. Executives and senior managers set the incentives, metrics, and cultural norms that determine how maintenance organizations behave.

Leaders must move beyond measuring:

- Number of work orders completed

- Percentage of preventive maintenance compliance

- Maintenance budget utilization

Instead, leadership should emphasize:

- Reliability improvement trends

- Failure elimination effectiveness

- Maintenance cost per unit of output

- Asset availability aligned with business objectives

By reframing success metrics, leaders create space for maintenance teams to focus on value rather than volume.

The Strategic Advantage of Doing Less but Smarter Maintenance

Organizations that successfully reduce over-maintenance often experience a counterintuitive outcome: fewer tasks, lower costs, and higher reliability simultaneously. This occurs because maintenance effort is redirected toward activities with demonstrable impact on failure prevention.

In such organizations, maintenance becomes a strategic capability rather than an operational burden. Technicians are empowered to analyze problems rather than merely execute schedules. Data is used to inform decisions rather than justify activity. Reliability improves not because more is done, but because what is done matters.

Over-Maintenance as a Barrier to Digital Transformation

Many digital transformation initiatives in asset-intensive industries fail to deliver expected value because they are layered on top of flawed maintenance philosophies. When over-maintenance exists, digital tools often accelerate inefficiency rather than eliminate it.

Automated work order generation, sensor alerts, and AI-driven recommendations must be governed by sound reliability principles. Otherwise, digitalization simply scales the problem of over-maintenance at greater speed and cost.

Reframing Maintenance as a Value System Rather Than a Task System

To overcome over-maintenance, organizations must fundamentally reframe how they view maintenance. Maintenance should not be defined by tasks, intervals, or checklists, but by its contribution to business outcomes.

This shift requires:

- Continuous review and elimination of low-value tasks

- Strong collaboration between operations, engineering, and maintenance

- Investment in analytical capability and workforce competence

- Leadership commitment to evidence-based decision-making

When maintenance is treated as a value system, over-maintenance loses its justification.

Conclusion: Over-Maintenance as the Most Expensive and Least Recognized Failure Mode

Over-maintenance represents one of the most costly yet least acknowledged failure modes in modern asset management. It consumes resources, degrades reliability, distorts data, and undermines workforce effectiveness—all while masquerading as prudence and diligence.

As competitive pressure increases and margins tighten, organizations can no longer afford maintenance strategies based on habit, fear, or legacy assumptions. The path forward lies in disciplined reliability thinking, data-driven maintenance decisions, and leadership willing to challenge the notion that “more” is inherently better.

In the future of asset-intensive operations, maintenance excellence will not be measured by how much work is done, but by how effectively failure is prevented.

Company