A Scholarly Examination of Overlooked Assets, Latent Risk, and the Strategic Role of CMMS for Plant Managers

Abstract

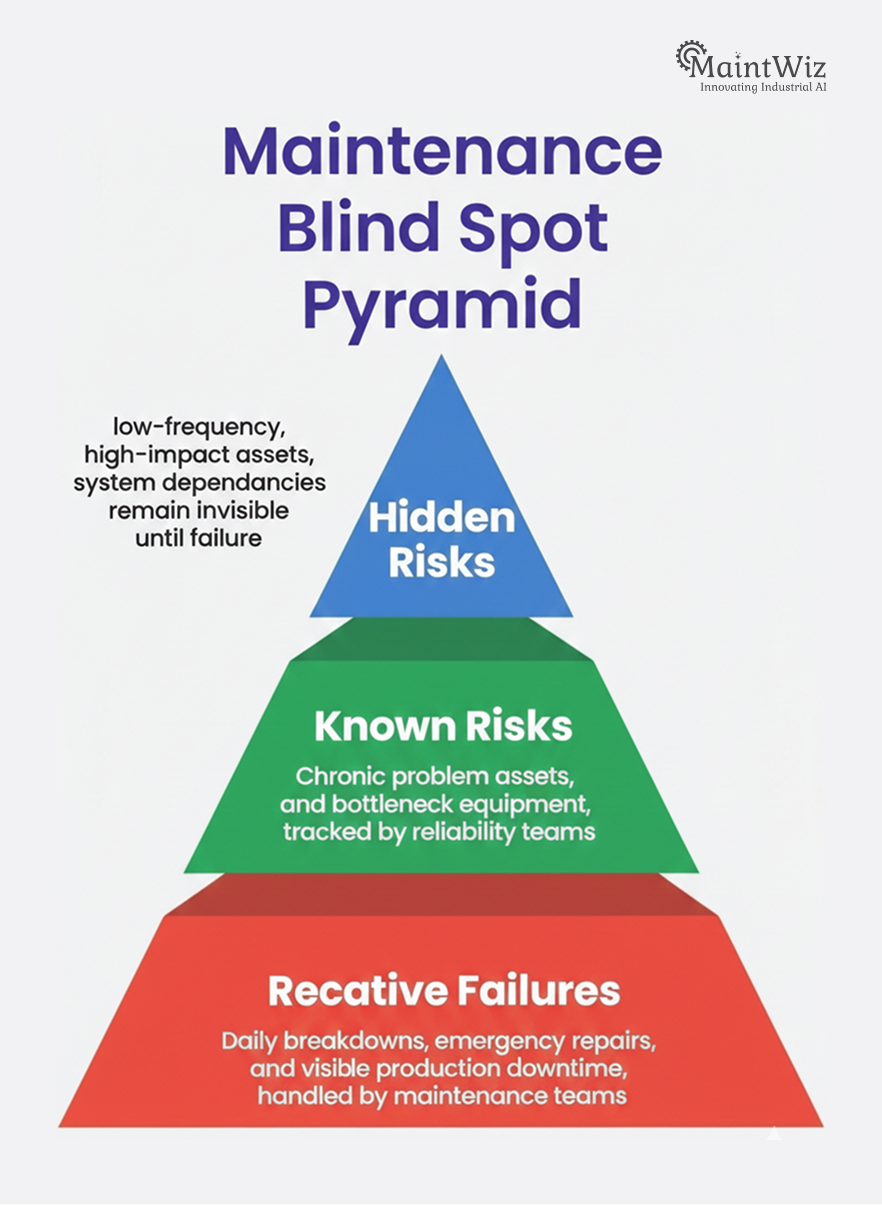

In industrial plants, maintenance and reliability strategies traditionally prioritize assets with high failure frequency, visible downtime, or significant historical cost. While this approach is logical, it unintentionally creates a critical blind spot: assets that rarely fail but possess high systemic impact. This article argues that the most dangerous asset in a plant is often the one that is ignored—not due to negligence, but due to its perceived reliability and absence of historical failure signals.

This paper explores the technical, organizational, and managerial reasons such assets escape scrutiny, examines their disproportionate impact on safety, production, and financial performance, and positions modern Computerized Maintenance Management Systems (CMMS) as a foundational enabler for identifying and managing this hidden risk. The discussion is aimed at plant managers and reliability leaders seeking to strengthen operational resilience through structured asset intelligence.

Introduction: Rethinking Asset Risk in Modern Plants

Plant managers operate in environments characterized by increasing production demands, tighter margins, aging infrastructure, and heightened expectations for safety and compliance. Within this context, maintenance strategies are often optimized around visible problems: frequent breakdowns, high maintenance costs, and chronic bottlenecks.

However, operational disruptions in many plants do not originate from these well-known problem assets. Instead, they frequently stem from assets that have historically performed well and therefore receive minimal attention. These assets remain outside rigorous maintenance strategies until a failure occurs, often with severe consequences.

This article challenges the assumption that reliability is synonymous with low failure history and proposes a more nuanced understanding of asset criticality—one that accounts for system dependencies, operational context, and latent risk.

Understanding the Concept of Ignored Assets

Defining an Ignored Asset

An ignored asset is not necessarily undocumented or unmanaged. Rather, it is an asset that lacks continuous scrutiny because it has not historically caused problems.

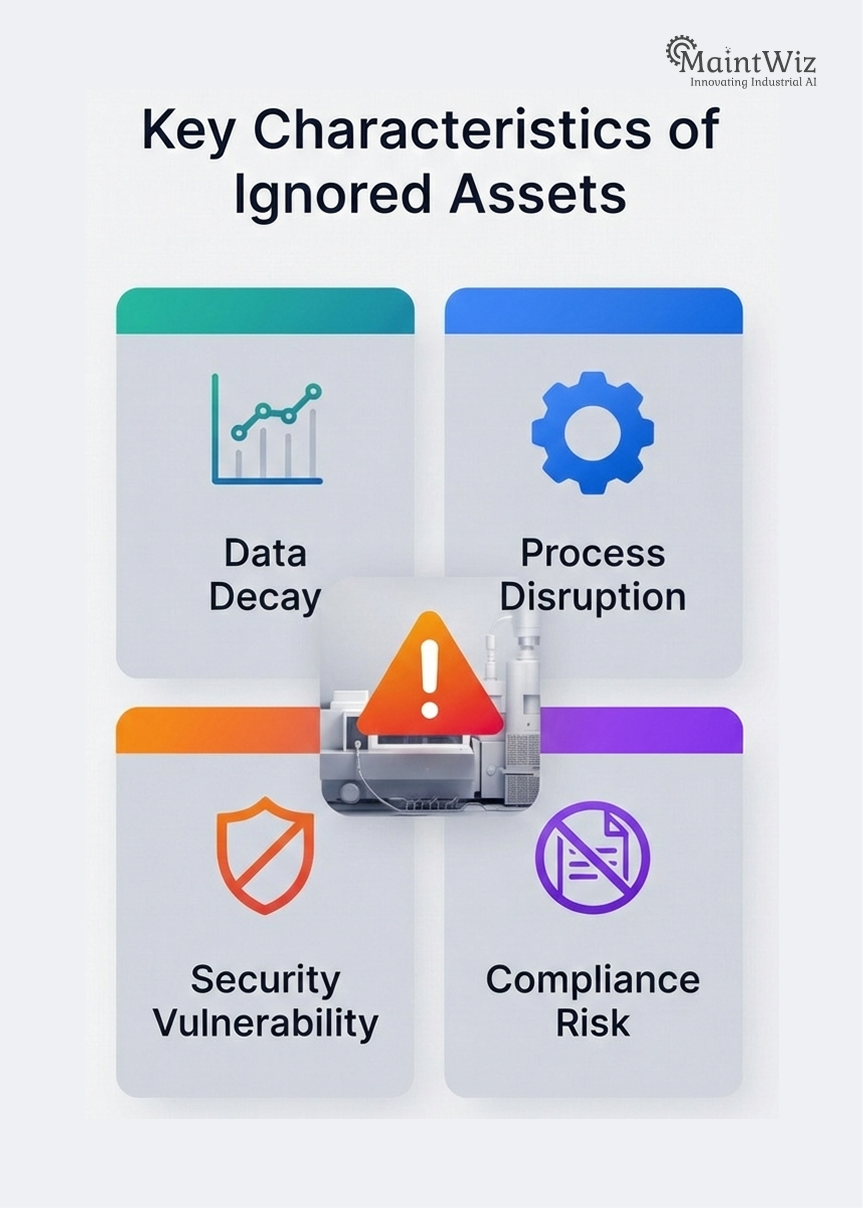

Key Characteristics of Ignored Assets

- Low Failure Frequency: The asset rarely appears in breakdown or downtime reports.

- Minimal Maintenance Activity: Preventive or predictive tasks are limited or absent.

- Assumed Reliability: Operational teams believe the asset is inherently stable.

- Low Visibility in Reviews: The asset is rarely discussed in reliability meetings.

These characteristics create an illusion of safety that can persist for years.

Why Ignored Assets Are Inherently Risky

Reliability Is Contextual, Not Absolute

Reliability is often treated as a static attribute of an asset. In reality, it is dynamic and influenced by operating conditions, load changes, upstream and downstream dependencies, and maintenance interventions.

Drivers of Hidden Risk

- Operating Beyond Original Design: Assets may be subjected to higher loads or longer run times than originally intended.

- Process Changes: Modifications elsewhere in the system can increase dependency on a previously secondary asset.

- Aging Without Oversight: Even robust assets degrade over time when condition is not actively monitored.

An asset’s past reliability does not guarantee future performance under evolving conditions.

Low-Frequency, High-Impact Failures

The Risk Profile of Ignored Assets

Ignored assets typically exhibit a failure pattern characterized by rarity and severity. While they do not fail often, their failure impact is substantial.

Attributes of High-Impact Failures

- Wide Operational Impact: Failure may affect multiple production lines or utilities.

- Extended Recovery Time: Spare parts, expertise, or redundancy may be limited.

- Safety and Compliance Exposure: Failures can introduce unsafe conditions or regulatory non-compliance.

These failures often surprise organizations precisely because the asset was never considered critical.

System Dependency and Hidden Criticality

Asset Importance Is Defined by Dependency

Traditional criticality assessments often emphasize individual asset behavior rather than system-level interactions.

System-Level Risk Factors

- Shared Utilities: Assets supplying air, power, water, or cooling to multiple processes.

- Control and Automation Components: Devices whose failure disables entire control loops.

- Auxiliary Equipment: Support systems that enable primary production assets to function.

An asset’s true criticality emerges from what depends on it, not from how often it fails.

Organizational Factors That Reinforce Asset Ignorance

Cognitive and Cultural Biases

Human and organizational behavior plays a significant role in perpetuating blind spots.

Common Biases

- No-News Bias: Lack of incidents is interpreted as confirmation of safety.

- Firefighting Culture: Attention is focused on assets that generate frequent issues.

- Responsibility Diffusion: Assets without clear ownership receive less scrutiny.

These biases are rarely intentional, but they shape maintenance priorities over time.

Maintenance Strategy Limitations

Event-Driven Maintenance Models

Many maintenance programs rely heavily on historical events such as breakdowns and alarms.

Limitations of Event-Driven Approaches

- Reactive Orientation: Focuses on what has already failed.

- Incomplete Risk Representation: Does not capture latent or emerging risks.

- Delayed Learning: Insights occur only after failure.

While effective for managing known issues, such models struggle to identify silent vulnerabilities.

The Financial Implications of Ignored Assets

Invisible Maintenance Debt

Maintenance debt accumulates when necessary interventions are deferred or omitted, even if the asset continues to operate.

Characteristics of Maintenance Debt

- Delayed Cost Recognition: Expenses are postponed rather than eliminated.

- Risk Accumulation: Probability and severity of failure increase over time.

- Budgetary Shock: Costs materialize suddenly during failure events.

Ignored assets are common contributors to maintenance debt because they are rarely prioritized.

Impact on Plant Performance and Stability

Operational Consequences

When ignored assets fail, the consequences often extend beyond maintenance metrics.

Operational Impacts

- Unplanned Downtime: Extended outages disrupt production schedules.

- Quality Losses: Process instability affects product consistency.

- Resource Reallocation: Skilled personnel are diverted from planned work.

Such events erode operational predictability and resilience.

The Role of CMMS in Addressing Ignored Assets

CMMS as an Enabler of Asset Visibility

Modern CMMS platforms are designed to centralize asset information, maintenance history, and operational data.

Core CMMS Contributions

- Comprehensive Asset Registry: Ensures all assets are documented and structured, supporting long-term reliability planning through a modern CMMS implementation framework

- Historical Context: Maintains a consistent record of maintenance actions and observations.

- Work Management Discipline: Encourages standardized documentation of interventions.

Rather than exposing deficiencies, CMMS provides the foundation needed to reveal hidden risks constructively.

From Asset Tracking to Asset Intelligence

Evolving Use of CMMS

When used strategically, CMMS can support proactive risk identification beyond basic work order management.

Advanced CMMS Capabilities

- Criticality Reviews: Facilitates periodic reassessment of asset importance.

- Maintenance Coverage Analysis: Identifies assets with minimal or no maintenance plans.

- Dependency Mapping: Links assets to systems, processes, and production lines.

These capabilities allow plant managers to ask better questions about overlooked assets.

Integrating CMMS into Reliability Governance

Structured Review Mechanisms

CMMS data becomes most valuable when integrated into formal decision-making processes supported by reliability improvement and maintenance culture best practices

Effective Governance Practices

- Asset Review Cadence: Scheduled evaluations of low-activity assets.

- Cross-Functional Input: Inclusion of operations, maintenance, and engineering perspectives.

- Data-Driven Prioritization: Use of CMMS insights to guide resource allocation.

Such practices transform CMMS from a record-keeping system into a strategic support tool.

Preventing Surprise Failures Through Intentional Inquiry

Asking the Right Questions

Ignored assets are rarely discovered through dashboards alone. They are revealed through deliberate inquiry supported by CMMS data.

Key Questions for Plant Managers

- Which assets have minimal maintenance history but high system dependency?

- Which assets have not been reviewed despite changes in operating conditions?

- Which assets lack clear ownership or maintenance responsibility?

CMMS enables these questions to be answered systematically rather than anecdotally.

Developing a Balanced Asset Strategy

Combining Reliability and Risk Perspectives

An effective maintenance strategy balances attention between problematic assets and silent contributors to risk.

Strategic Balance Elements

- Failure Frequency Management: Addressing chronic problem assets.

- Impact-Based Risk Management: Identifying low-frequency, high-impact assets.

- Continuous Reassessment: Updating strategies as processes evolve.

CMMS supports this balance by providing a unified view of assets and activities.

Conclusion: From Ignorance to Informed Oversight

The most dangerous asset in a plant is rarely the one that fails often. It is the one that escapes attention because it has not yet failed. Such assets represent latent risk shaped by system dependencies, organizational behavior, and evolving operating conditions.

For plant managers, the challenge is not to eliminate uncertainty entirely, but to reduce surprise. Modern CMMS platforms play a critical role in this effort by enabling structured visibility, disciplined data capture, and informed inquiry. When used effectively, CMMS does not merely document maintenance—it supports foresight.

By shifting focus from reactive problem-solving to proactive risk awareness, plant managers can transform ignored assets from hidden liabilities into managed components of a resilient operation.

Jai Balachandran is an industry expert with a proven track record in driving digital transformation and Industry 4.0 technologies. With a rich background in asset management, plant maintenance, connected systems, TPM and reliability initiatives, he brings unparalleled insight and delivery excellence to Plant Operations.